How Bad Data Happens

by Andrew McCall

A lot of what we do as data engineers is fix things that have broken. Either we’ve been alerted to something having failed with that job again. Or some user or another is telling us that some value for a record is wrong.

How did we get here?

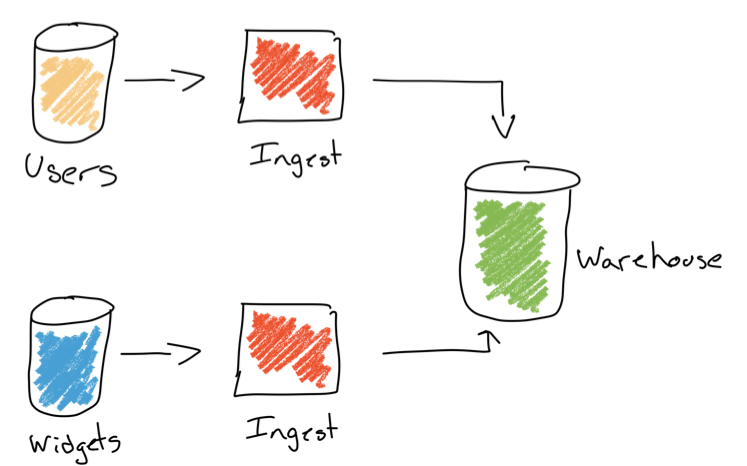

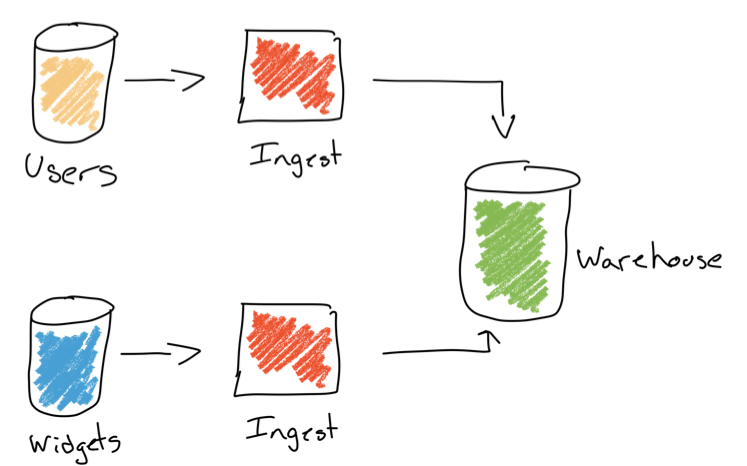

When you’re writing a web service that takes a value, you can force the user to give you one or reject their request as invalid. Data, is different, imagine you’ve got a warehouse that has data from a few micro-services and downstream some reporting.

We have a user service that holds some details about a user and a widget service that maybe monitors some IoT devices and sends an alert to the user’s mobile number if a widget stops working.

If the data from your user service comes in without a mobile number, what do you do? It doesn’t really matter how the required field got to be null, in the upstream and there are plenty of reasons it can and will happen, but for the sake of this scenario let’s assume it was because a developer introduced a “bug.”

I quote bug there, but it’s equally likely that what the developer introduced wasn’t a bug at all. The required field may have been required before but due to other system changes isn’t needed for some use cases anymore.

Now you have data flowing from one of the micro-services which is invalid. How do you handle that?

Well, you’ve got a few options, none ideal:

- Accept the broken data.

- Drop the record and continue

- Fix the data in flight.

I’m going to argue for all sorts of reasons (but not here) your least worst option is to maintain consistency with the source at least for ingestion purposes. So the last two in my opinion are out.

So what now? You’ve got a record that you’ve accepted as broken… before we get there… Do you even know?

How do you measure data quality?

Many organisations have some scripts that are run by an engineering team that let them monitor jobs for errors. Some maybe even have some more advanced reconciliation scripts they can run as part of the process to check the data. This is mostly for the consumption of the engineering teams monitoring the jobs and allows them to be notified that something has gone wrong.

These are generally good at spotting data that may be missing, but usually not so good at implementing business rules around the context, and more often than not consumers of the data are completely in the dark.

So most organisations, let’s be honest, only notice data quality issues when someone else notices and complains. It could be an analyst or even an end user. This is a pretty broken and pretty sorry state of affairs.

Tooling, is there light at the end of the tunnel?

Some organisations are starting to adopt DQ tools which do some form of data profiling. My problem with these tools is they’re focusing on data quality as a governance function, the same way we treated testing and QA decades ago. As something to centralise the rules around across a whole organisation so they can be applied consistently to all data. The idea being that if all data follows the same rules you can apply the same rules across the board, enforce them and even fix the data in flight.

I don’t only think this is the wrong way to do things, I think it’s a fantasy to think it’s even possible.

Let’s go back to our really simple example, I need to have a mobile number for a user so I can send them a text message when a widget has a problem. One potential “bug” a developer above could introduce would be to add groups and types of users. Now I can send an alert about a widget to multiple users and I can create a new type of user that is only concerned with billing. Now we have different user types and we really don’t need a mobile number for users concerned with just billing, so the developer makes the field optional. All her tests pass and the code works and being ever diligent and thorough she’s even added checks to prevent setting up alerts to users without mobile phones.

How is this a problem? Well keeping with the example maybe there is a KPI and report around alerts per user or alerts per widget. Maybe it’s on a monthly dashboard or on an exec pack and there is no context around it and our backend and frontend teams have no idea it even exists. Let’s say we’re launching the new users features with a subset of users. Our team of decision makers will see one of two things:

- The number of alerts per widget in the system has increased! This feature is on fire, let’s launch it!

- The number of alerts per user is lower, our users must hate this feature let’s can it.

Depending on your business model, charging per seat or per alert one or both of these results aren’t going to give you an accurate view of the world. Which will lead to bad decisions.

Would a DQ tool help?

It depends, if the quality rules enforced the fact that a user had to have a mobile number the feature may have failed testing. But there are some assumptions and problems here.

First the DQ tools and rules would have to exist and have to be in sync between a production and staging environment. This would add development complexity and slow the development teams down when they encountered something like this, likely late in a testing cycle.

They’d have to reach out to a central team and figure out how they could get the rules changed, the DQ team would need to know where a rule was used and why and would likely need to be part of every new feature. They’d also need to get whoever the report owner was to look at making changes to the report.

More hand-offs, more meetings and someone would be too busy.

There’d be no way for the tool to “clean the data” in flight, it simply doesn’t exist so all it could do would be reject the data forcing users to give a mobile phone number when one wouldn’t ever be used.

A better way?

Data quality should be something we treat like metrics we gather for other services. You track memory usage, latency and requests per second or micro-services and when things start to go wrong someone gets a notification. It’s not a central function, but part of the job for engineers or SREs.

In a data world this should be part of the job for engineers, analysts and data scientists. What we really need is tools that rather than trying to enforce business rules give us better insight into the current state of data.

Just like we’ve moved data democratization tools towards empowering consumers of data to discover and remix data, analytics and insights we should do the same with data quality. It’s not just for engineers or governance it should be part of everything we do.

Call it DataOps or something else, the tooling and mindset does need to shift more towards how we’ve shifted with software development in general, move fast but know when you break things.

Subscribe via RSS